Head Strength & Conditioning Coach, United States Tennis Association Player Development, iTPA Master Tennis Performance Specialist (MTPS)

Mark Kovacs, PhD, FACSM, CSCS*D, CTPS, MTPS

Executive Director, International Tennis Performance Association & CEO, Kovacs Institute

Introduction

Proposal of the RETURN TO TENNIS (RTT) MODEL

To determine an effective return from this unique environment we are proposing the RETURN TO TENNIS MODEL (RTT) with a focus on “High Performance Players.” This model has used data collected from two female professional tennis players during the 2018/2019 seasons as our reference data. This will allow us to utilize real data and showcase how to prepare for Return To Tennis scenarios using previous data as a guide for individualization and personalization needed for high performance players.

Key Findings from Workload Data Collections

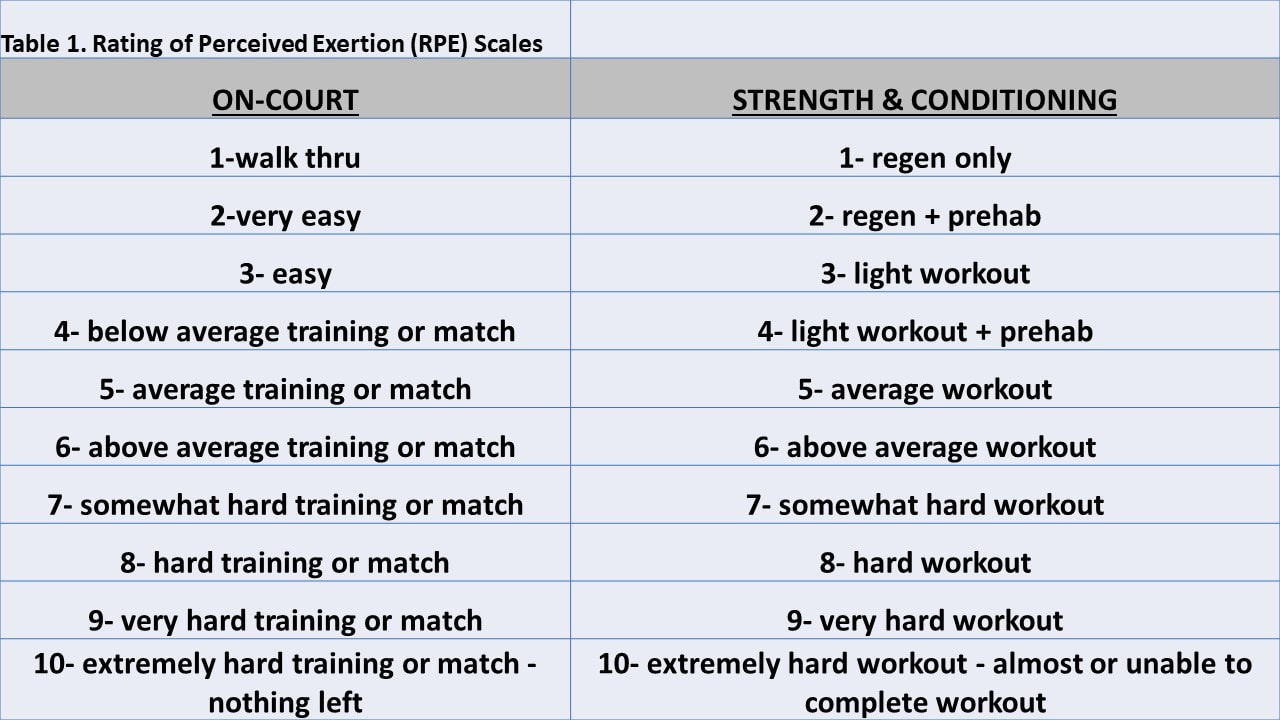

By monitoring two female professional tennis players (Player A & Player B) daily workloads for 52 to 53 weeks respectively in 2018-19 we were able to utilize this data to prepare a model that could be utilized for future players when planning to return to tennis. Player A was a Top 100 WTA ranked individual and Player B was a Top 200 WTA individual. Both players (and each player’s coach) were instructed to report session duration and Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) for each practice and physical activity session. Data collection started at the beginning of pre-season training in October 2018 for player A and November 2018 for player B. Prior to the data collection, players and coaches were given specific instructions on how to accurately monitor and record RPE numbers (Table 1).

Both players had successful seasons without any major injuries that would interfere with a normal training and competition schedule. The workload was calculated using the formula:

Workload = session duration (in minutes) X session RPE

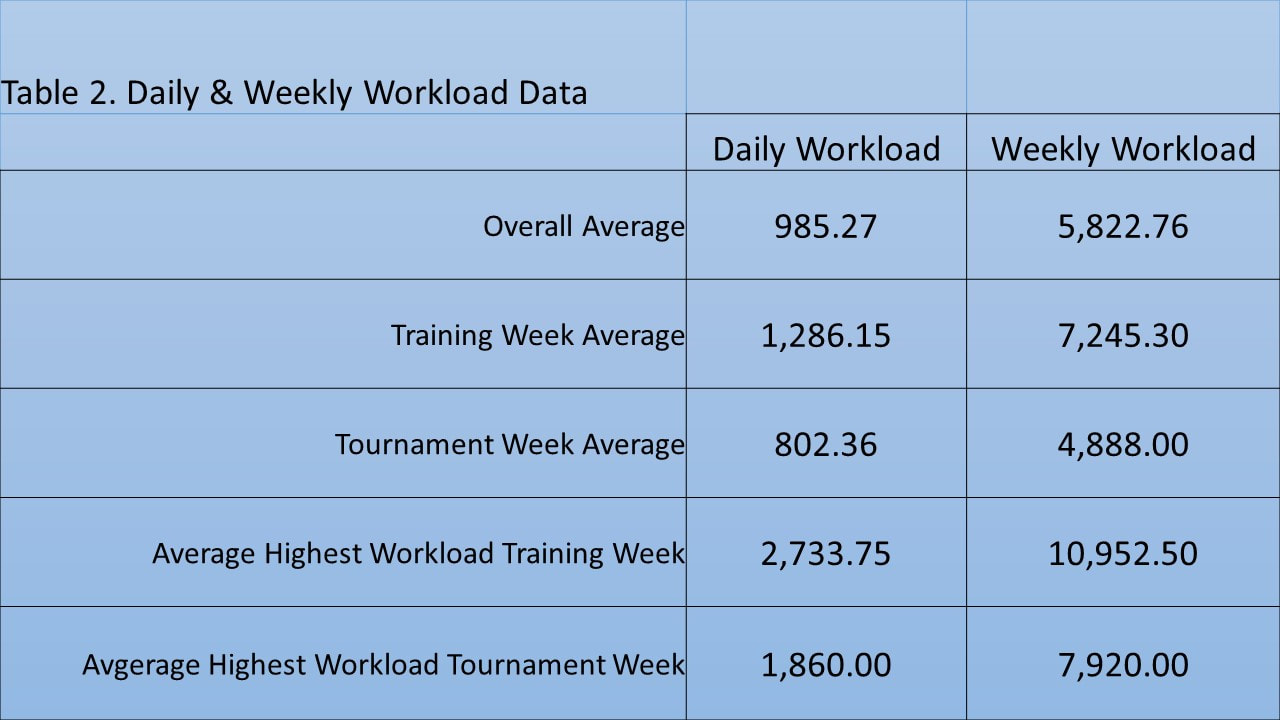

Each session workload was recorded daily and the sum of Monday through Sunday daily workload was calculated as weekly workload. Overall daily and weekly workload averages were 985.27 and 5,822.76, respectively (Table 2). Other key findings are summarized on Table 2. There were significant differences in players’ workloads between “training week” and “tournament week.” If a player played any matches as a part of the tournament, the week was considered a “tournament week.” In tennis, the tournaments are usually week-long events, and unfortunately each tournament may have various number of matches based on how many matches a player may win. In many tournaments players may only play one match in one week (tournament). Therefore, the tournament week workloads are highly variable. Although over 95% of all sessions were recorded throughout the year, a very small number of missing sessions did occur due to travel and communication challenges, especially when unplanned sessions occurred. These key findings give coaches and support staff valuable information on how to work with high performance female tennis players. This information could be utilized and applied for tennis players periodization plans as most of the tennis tournaments are played in the same formats (best of 3 set matches lasting between one and four hours in length).

Understanding A Player's Current Condition and Determining The Appropriate Initial Process

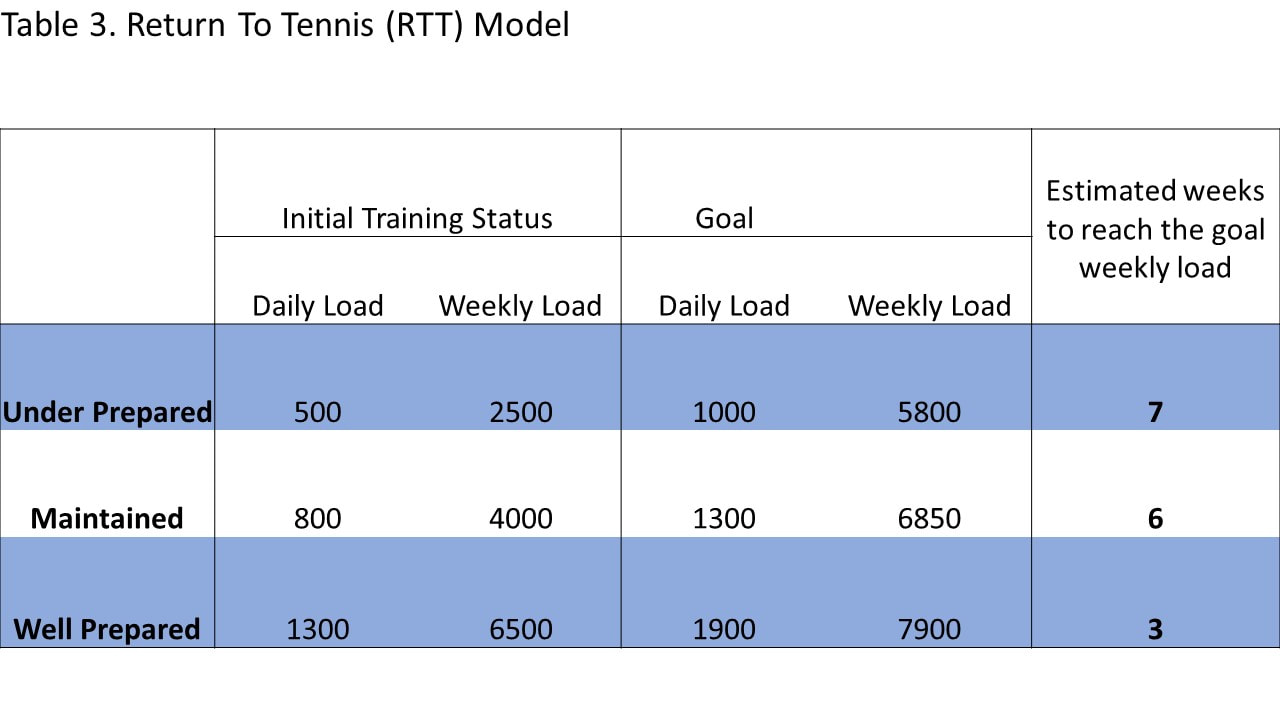

1. Under Prepared: a player has done minimum workload; for examples, 500 daily workload and 2500 (500 x five days a week) weekly work load.

2. Maintained: a player has maintained normal or close to average workload; for examples, 800 daily workload and 4000 (800 x five days a week) weekly workload.

3. Well Prepared: a player has been sustained close to normal training week workload; for example, 1,300 daily workload and 6,500 (1,300 x five days a week) weekly workload.

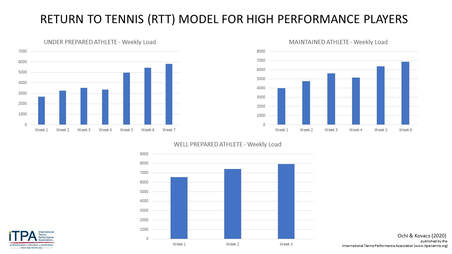

Table 3 summarizes initial training status, goal training loads, and estimated weeks to reach the goal weekly load for each category of players. The examples of the initial daily workloads for the Maintained and Well Prepared players are based on the findings from the two female professional players. The average of daily workload during the tournament week (802.36) and average of daily workload during the training week (1,286.15) are shown respectively (Table 2).

Acute Chronic Workload Ratio Calculations

Return to Tennis (RTT) Plan Examples

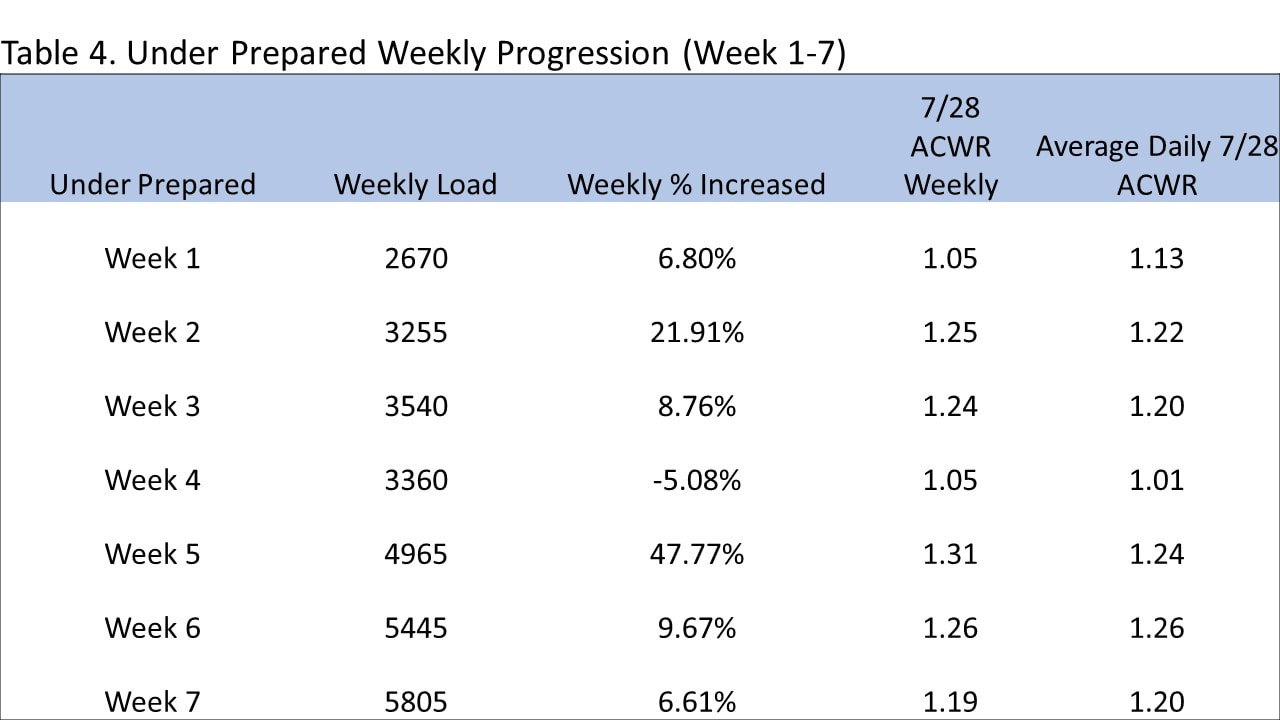

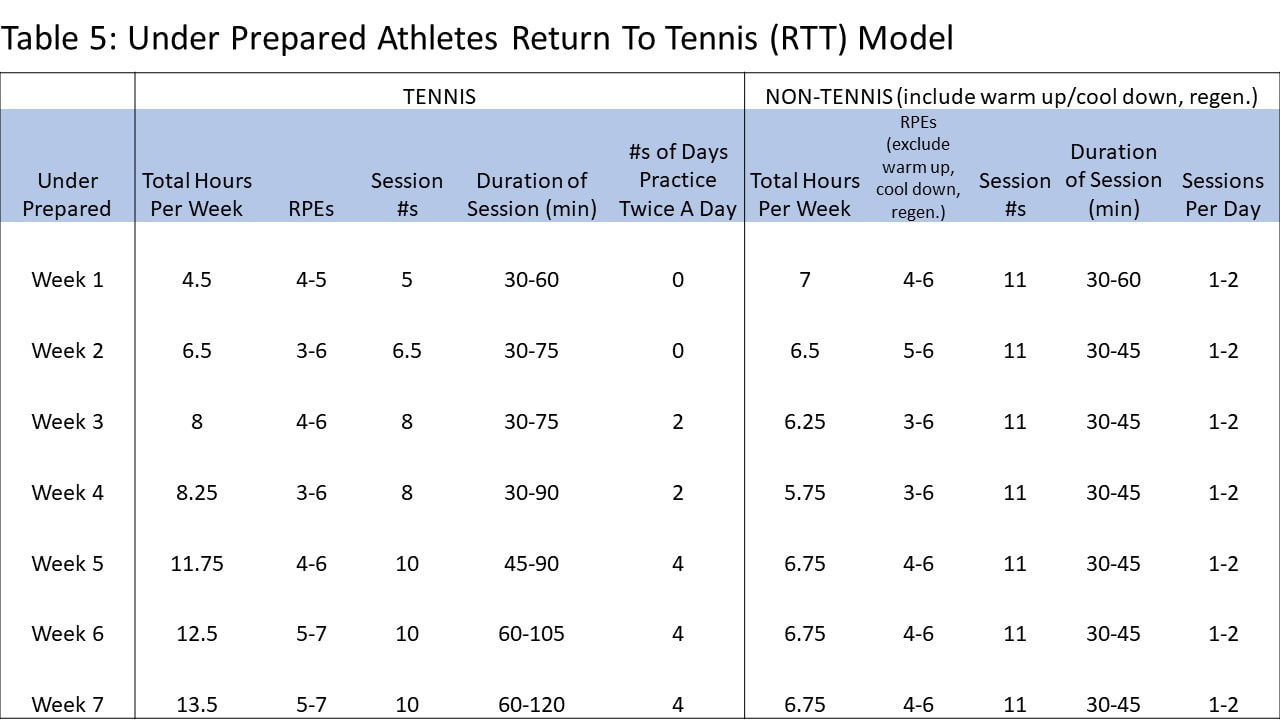

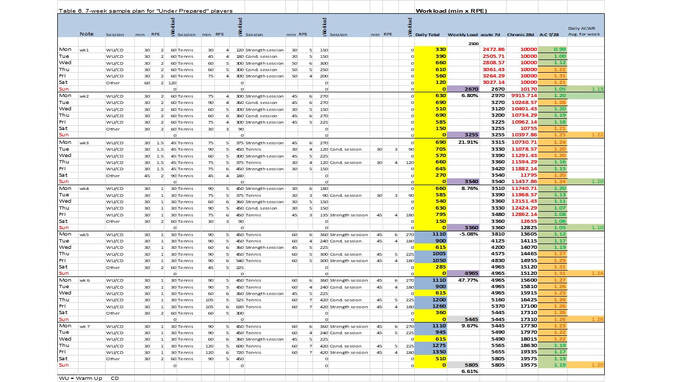

If a player has not been able to practice and training regularly and only perform minimum workloads prior to return to practice and training, the beginning workload for the week one of the practice and training should be very low. In general, 10% training load increments have been recommended in many environments when returning to play from injury, etc. However, the potential weekly workload increment for the week one could be less than 10% from previous week (as if the player has been doing minimum practice and training, such as 500 daily workload and 2,500 weekly workload). In our presented model week one weekly workload is increased by only 6.8% (table 4). The examples of tennis and non-tennis frequency, RPEs, sessions numbers, and duration of the each session can been seen in Table 5. The non-tennis sessions include warm up, cool down, regeneration / recovery sessions. However, non-tennis RPE examples are only for actual training (strength and conditioning) sessions and does not include warm up and cooldown. If a player is under prepared, the main goal is to rebuild chronic workload so that the player will be able to perform higher workloads safely and eventually achieve the goal daily and weekly workloads. The goal daily & weekly workloads are set to 1,000 daily workload and 5,800 weekly workload in this model. The daily goal workload of 1,000 is selected as it is an example of higher-intensity sessions. The 5,800 goal weekly workload is based on the finding from the two female professional players as the overall average weekly workload of 5,822.76 (table 2). In this model, it takes about seven weeks to achieve the goal workload. The summary of seven weeks weekly workload progressions can be seen in Table 4. The full summary includes daily plans is in Table 6. Because of the initial training status, somewhat aggressive workloads are needed to apply to achieve the goal workloads and be ready for even higher workloads or potential competitions. At the same time, the workload should be apply and increase safely to maximize training benefits and minimize likelihood of injuries. Therefore, second and third week’s workloads are significantly higher than the first week, especially second week (increased by 21.91% from week one). It has been recommended to keep the ACWR between 0.8 and 1.3 in many team sports and some in tennis as well. This recommendation has some support suggesting this may reduce the likelihood of injuries. Even though the weekly workload increment is high, the ACWR is kept under 1.3. This is important to recognize that higher than 10% increases can be achieved while keeping ACWR in manageable and acceptable ranges. Because of the aggressive increments of workloads for the first three weeks, the workloads for week four should maintain or slightly lower than week three. However, the weekly and daily averages of ACWR stay above the 1.0. The workload for the week five is increased by 47.77% in this model. It seems a large jump. However, the daily average ACWR stays below 1.3 and the weekly ACWR is only slightly higher than 1.3. The following week continues to have a high ACWR of 1.26 for both weekly and daily average. The previous four weeks of training loads should provide sufficient experience and prepare the players to go through high ACWR days and week during week five and six. This is similar to “shock” block or microcycle that has been utilized in soccer and other sports. As the results at the end of the week seven, the player should achieve the goal workload safely and efficiently in this model.

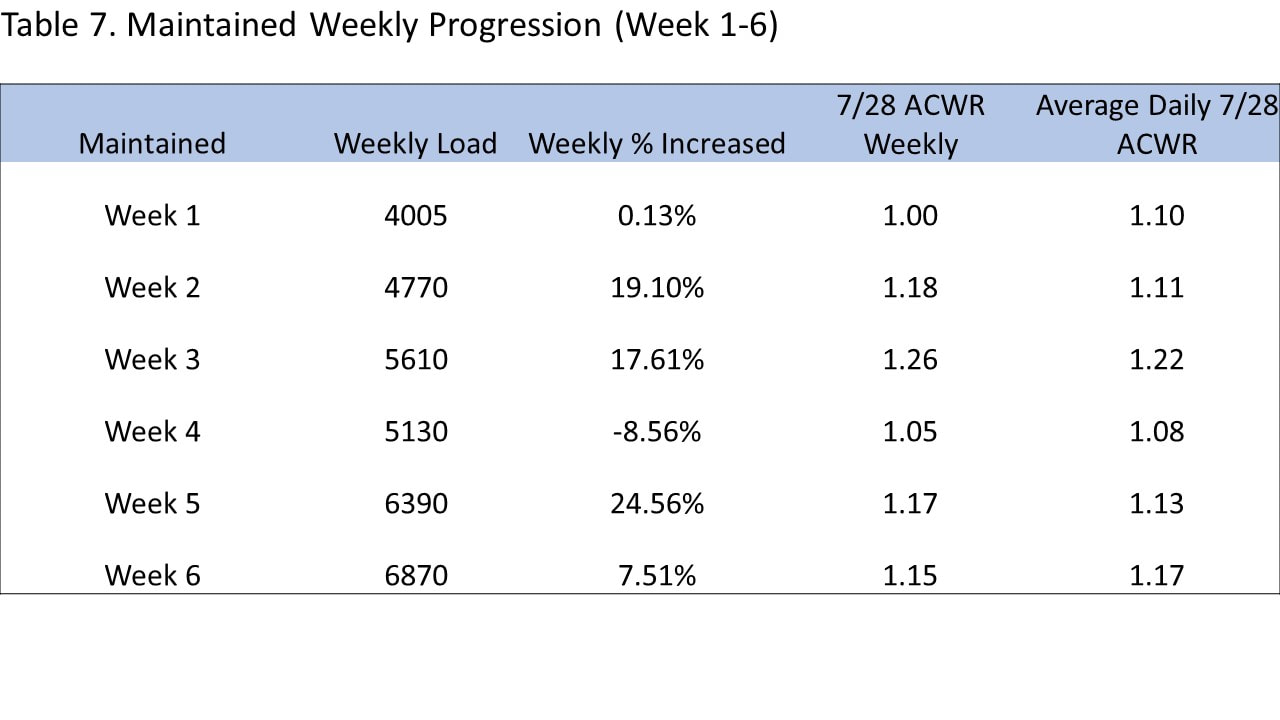

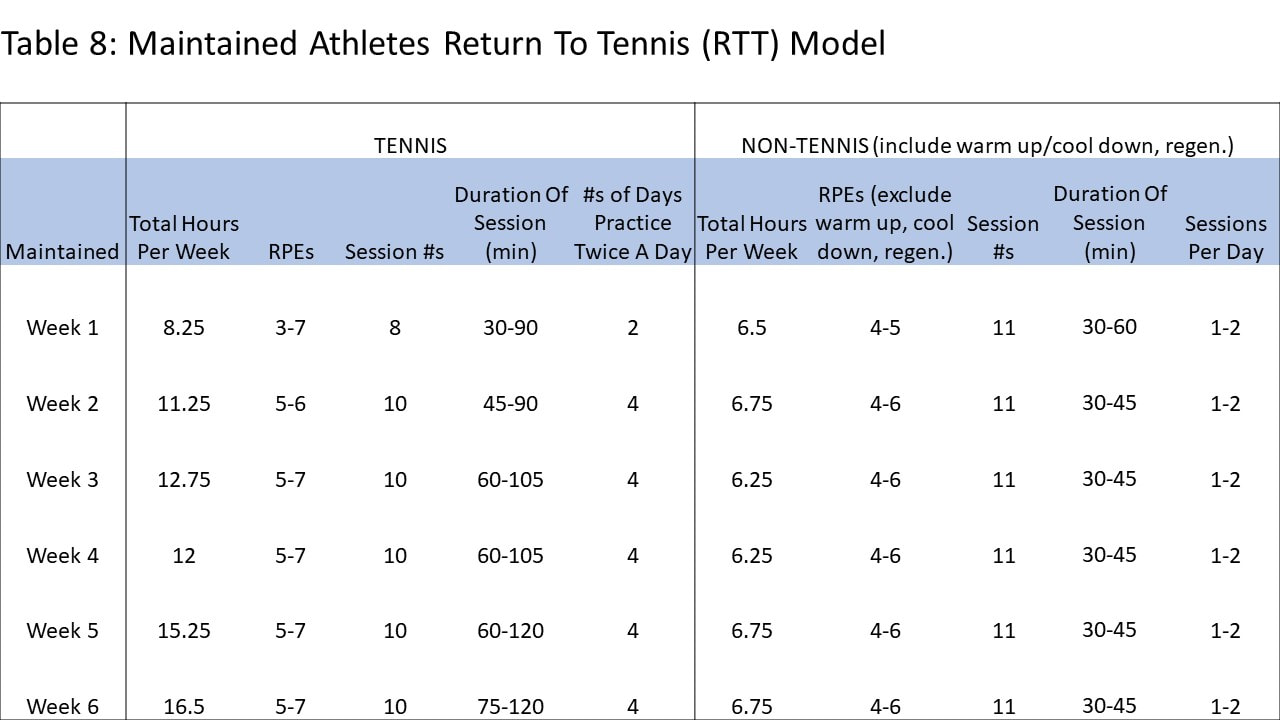

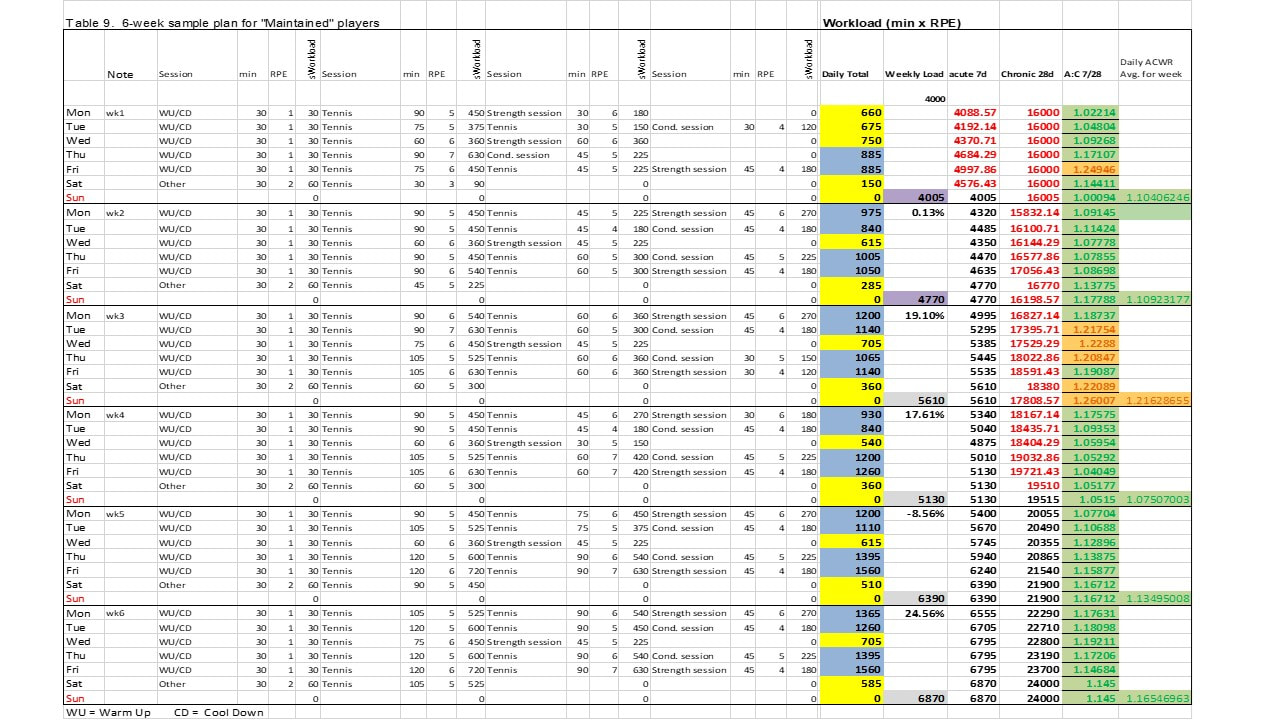

If a player has been able to maintain normal or close to average workload prior to return to train and practice, the player should be able to start higher workload than the under prepared players from week one. Therefore, the initial daily workload is set as 800 in this model. This is based on the average tournament week daily workload from the two female professional players’ data (Table 2). The goal workloads for the “maintained” players are 1,300 daily workload and 6,850 weekly workload. The goal daily workload is based on the average training week daily workload of 1,286.15 from the female professional tennis players’ data (Table 2). The goal weekly workload is a middle point between the under prepared goal weekly workload of 5,800 and the well prepared goal weekly workload of 7,900 (Table 3). The weekly progressions are similar to the ones for the under prepared players. The week one starts slow, followed by very aggressive week two and three, a slightly lower workload for the week four than week three, very aggressive week five, and moderate increment for the week six (Table 7). Because of the higher initial workload than under prepared players, a player for this model should achieve the goal workload safely and efficiently by the end of week six. The weekly ACWR and average daily ACWR are below 1.3 for the entire six weeks. The examples of tennis and non-tennis frequency, RPEs, sessions numbers, and duration of each session can been seen in Table 8. The full summary includes daily plans is in Table 9.

3.Well Prepared Athletes

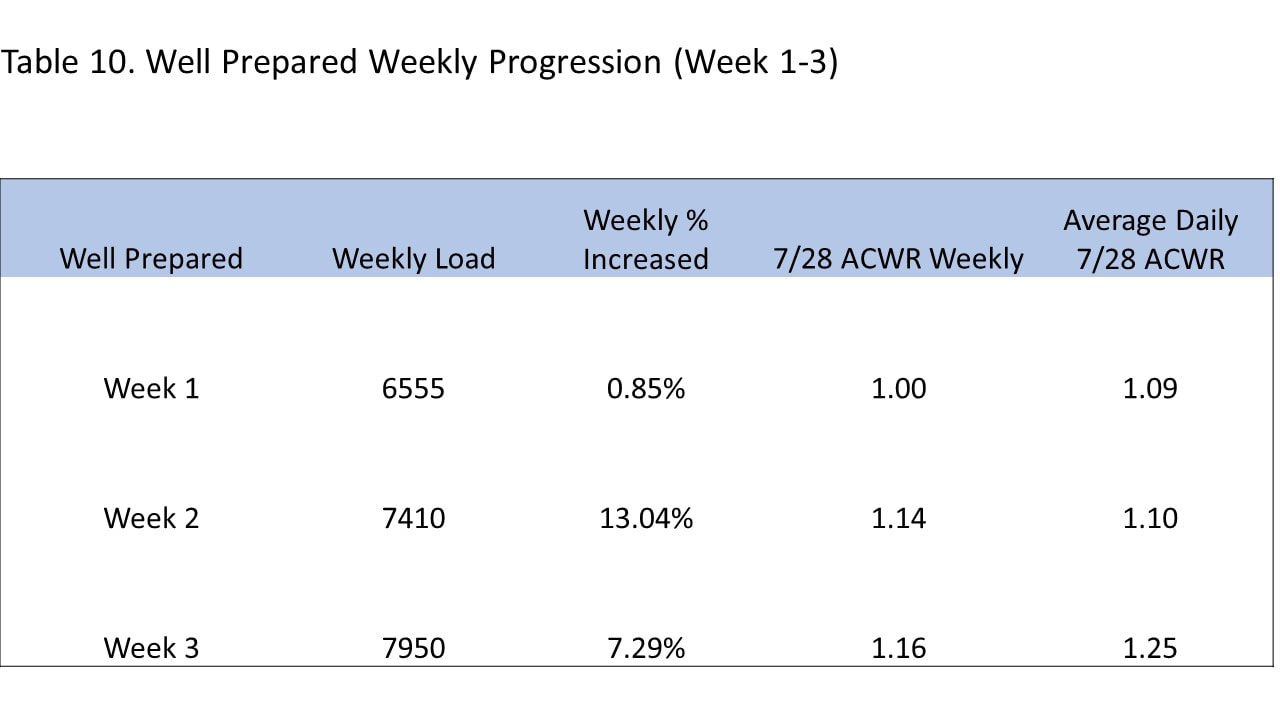

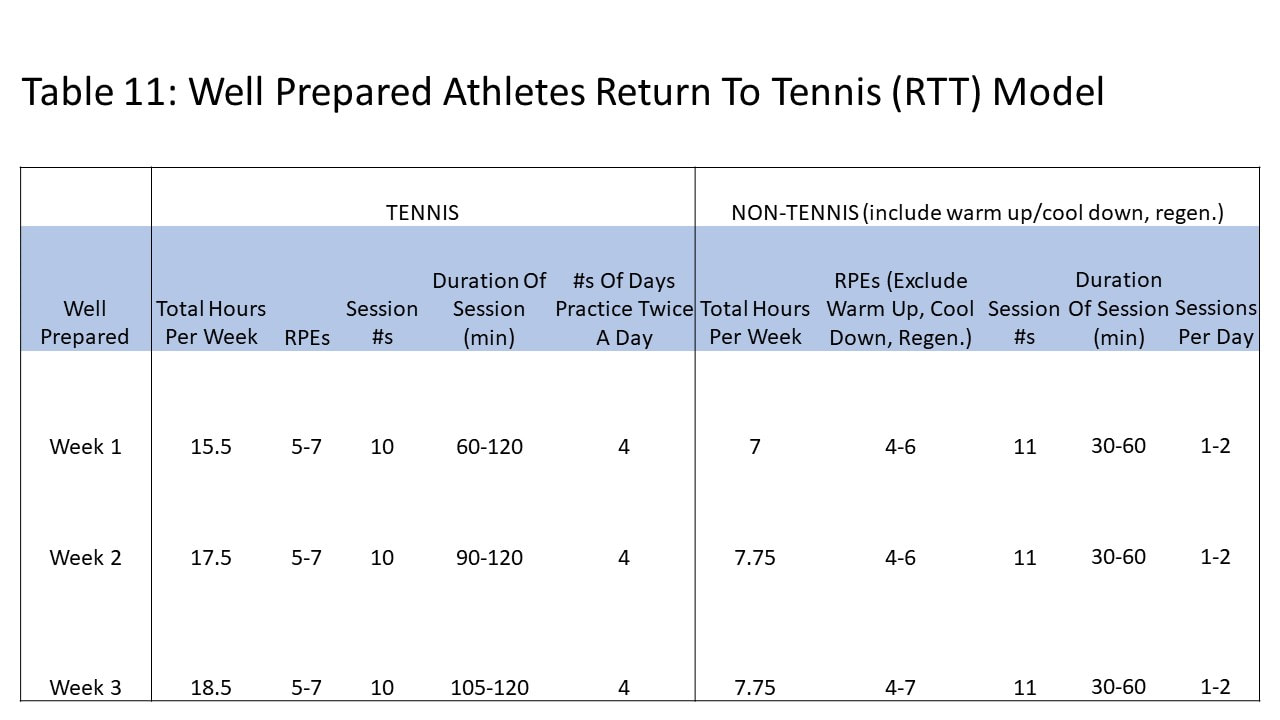

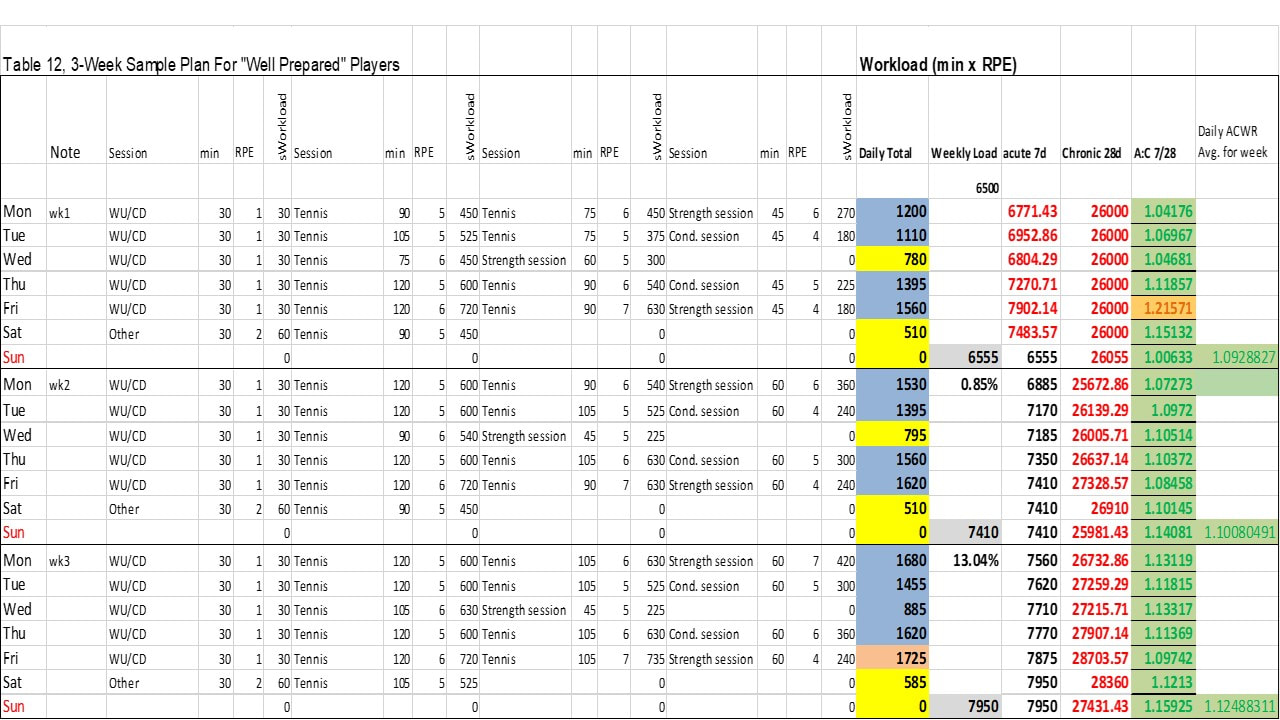

If a player has been able to sustain close to normal training week workload prior to return to train and practice, the player should be ready for high workload training and practice rather close to a normal training week. Therefore, the initial daily workload for the “well prepared” players is set to 1,300 that is similar to average training week daily workload from two female players’ data (Table 2). The goal daily and weekly workloads (Table 3) are based on the average highest daily and weekly workloads during the tournament week 1,860.00 and 7,920.00, respectively from the female professional tennis players’ data (Table 2). Under this model and due to the well prepared player’s initial training status, it should only take three weeks to achieve the goal daily and weekly workloads. This highlights that a three week training block may suffice to train an athlete before tournament play who comes into this period “well prepared.” This would provide similar workloads to the potentially high workloads for the tournament week (Table 10). The examples of tennis and non-tennis frequency, RPEs, sessions numbers, and duration of each session can be seen in Table 11. The full summary includes daily plans in Table 12.

Practical Application Of This Data For High Performance Players

- Educational Sessions With Players and Coaches: The purpose of the educational session is to provide a clear and concise explanation on the RPE scale and to make sure agreement exists in the various levels for both players and coaches. Ideally, any session should be within ±1 RPE between a players’ perspective and that of the coach. This ensures that both the coach and player are under the same subjective perspective of how hard the training sessions “feel.” A secondary benefit of the RPE scale is that it can expose unexpected stress that players might be experiencing, especially when there is a significant difference between coaches planned session RPE and players actual RPE numbers.

- It is also helpful to use other questionnaires, assessments, and possibly wearable technologies. The information from other sources (questions, results and devices) may not only provide additional internal or external load metrics but also potentially confirm what session minutes x RPE workloads may show and provide even more data to help with decision making.

- The week one of return to play and training should be almost same as the previous weeks of training workloads (avoiding any spikes in workload early in the process is paramount). This is why it is so important to understand what players have done in the previous two to four weeks prior to return to formal training. The first week will help to understand players’ actual physical status and provide more accurate information to adjust plans and workloads for the upcoming weeks. The concept here is go slow and ramp up appropriately.

- The returns to play and practice plans have to be customized for each player using all available data. However, each player has a different initial training status, genetic capabilities, responses to training varies considerably and that is why constant daily monitoring is needed.

- It is important to remember that any other stressors (academics, family, financial, etc.) might influence a player’s physical and mental condition. If players have been only training on their own without coaches, presence of the coaches could increase training and practice session intensity automatically. Return to a more normal training environment will increase the general intensity even if the total time of workouts may be the same. Important to factor this into the plan.

Conclusions

To learn more about how to use data and science to help structure training programs for tennis athletes at all levels of the game, please check out the International Tennis Performance Association (iTPA) educational programs including the Tennis Performance Trainer (TPT) Certification program focused on the tennis coach and the Certified Tennis Performance Specialist CTPS) which is aimed at the strength and conditioning coach, physical trainer, athletic trainer, physical therapist, chiropractor, medical doctor or other healthcare provider working with tennis athletes. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed