Measurement of initial leg power can be correlated to leg strength. Hewit et al. (2012) tested single leg countermovement (SLCM) jumps vertically (SLCM-V), horizontally (SLCM-H), laterally (SLCM-L) with either legs. The largest leg discrepancies were SLCM-L. Lockie et al. (2014) found some correlation between lateral power and COD but lateral jumps were not the strongest predictors of the COD test. Young et al. (2002) found that COD was related to the outside reactive leg strength. For example, athletes averaging 24% stronger in the right leg were 4% faster moving to the left; moving to the right was not correlated with leg strength. Lateral movement due to unilateral leg strength was not considered a factor unless there was a significant strength difference between legs. In addition, Young et al. suggested reactive leg strength was a greater factor than concentric leg strength. It was suggested that technique and perceptual factors also affect lateral speed. Both studies (Lockie et al., 2014; Young et al., 2002) look at linear speed with 20-60° as the range of COD which represents more traditional cutting in team sports. A test for 3 m COD and acceleration (CODAT) was devised using 45˚ and 90˚ COD (Lockie et al., 2013).

As opposed to many field sports, tennis involves significant movement back to the origin which implicates many 180° CODs. Therefore, unilateral leg reactive strength might be a greater factor in tennis. Hoppe et al. (2014) indicated high acceleration and deceleration with 180˚ COD was a major characteristic of tennis movement. Habibi et al. (2010) found single leg hop power was correlated with 10 m sprints. It was found that a triple single leg hop was even a better predictor for 10 m sprint times. That suggests reactive strength in landing with rapid muscle contraction and stored elastic energy is critical. In addition, the explosiveness movement from a previous jump, hop or bound is more critical for acceleration than from a standing position.

In tennis, lateral speed is initially generated after an athlete makes a modest vertical jump or split-step with a resultant lateral bound. Although Lockie et al. (2014) suggested lateral jumps were not the strongest predictors of 20-60˚ COD ability, 180˚ COD were not investigated. Therefore, lateral jumps may still remain a predictive test for tennis. By definition, a hop is when the take-off and touchdown is done off the same leg and the distance covered is relatively small. A jump is either one- or two-legged but the distance is relatively greater. A bound is when the take-off leg and touchdown leg are opposite legs. With that in mind, single leg lateral bounds for both legs can show promise for improving contralateral force production.

The well-known Pro Agility Test and 3 Cone Drill has been shown to be correlated to 10 m sprinting (Mann et al., 2016). Both can be useful for tennis testing since they utilize 180˚ COD and acceleration/deceleration. In addition, as Young et al. (2002) and Habibi et al. (2010) suggested, reactive unilateral leg strength can be important. Figure 1 shows a simple single leg lateral jump (SLLJ) in which a countermovement is allowed and the takeoff and touchdown leg are the same. Measurements should be on the outside edge of the foot or shoe (green line). Lateral bounds in both directions should be executed and measure from a best of three bounds.

Wall Drives and Runs

Wall drives and runs are shown in Figures 3 and 4. In the crossover wall drive (Figure 3), the athlete crouches and leans with the inside shin angled towards the wall. A cross-over step is taken with the outside leg. The athlete can repeat in sets of 10 and then switch direction and legs. The lateral wall run is shown in Figure 4 has the athlete more upright. This exercise can be done with different number of steps: a) 1 step - lifting only the inside leg, b) 2 step, c) multiple step. A coach or another athlete can call the number of steps, e.g., “three,” or “four.”

Lateral Wall Drills

The single leg lateral jump test is often used as a repeated bounding exercise alternating legs (aka “alley hops”). Another set of simple movement exercises are wall drives and runs. Many athletes have trained with forward wall drives where the athlete faces a wall and leans forward at 45˚ with hands outstretched supporting the body against the wall. For tennis, lateral wall drives and runs are specifically applicable. Lateral wall drills allow the athlete to shift the center of gravity applying horizontal lateral force, while maintaining balance using a wall or fence.

The simplest drill is the lateral wall hold using either leg (Figure 3) which is also good for core and hips strength. The athlete leans sideways into a wall (fence is more difficult). The athlete lifts either leg with the knee up to the hips and maintains the leaning position for a few seconds and then may switch the legs and hold that position with the knee up for a few seconds. The athlete repeats leaning the other side. Once the athlete is comfortable with the positions, the athlete can do a second drill: lateral wall runs with sets of 2-6 rapid alternating steps. Repeat for a set of 6-8. Then the athlete does another set on the other side.

Most split-steps in tennis involve a vertical component with landing first on the leg farther away from the intended direction and the other leg taking a lateral step with the toe pointing toward the intended direction. For training, the following exercises are useful:

Figure 6. Vertical single leg hop + lateral bound

Contrast Resisted and Assisted Training

Contrast training refers to varying loads with similar movement or exercises. For speed training, often contrast training involves only slight changes in force (Dintiman, 2020; Mann & Murphy, 2018) since larger forces can alter mechanics to alter movement. A classic contrast training is performing the same resistance exercise (e.g, leg press) with different loads. A classic contrast training for speed involves running uphill and downhill but at modest angles so not to alter running mechanics (Dintiman, 2020). Bungees and resistance bands can provide assistance or resistance forces without dramatically altering lateral movement. Shown in Figure 9 shows the bungee-assisted lateral explosion. Attached a bungee high so it pulls the athlete laterally but also upwards. Use a split-step into a crossover step and sprint 2-3 m. Figure 9 shows the bungee-assisted exercise. For bungee-resisted lateral explosion, attach the bungee low on the fence (see Figure 10). The athlete can split-step into a crossover step, focusing on a more upwards pull upwards and away and from the fence.

Tennis movement is mostly lateral but athletes may have differences in movement to either side which should be trained. Movement in tennis is mostly short accelerations and decelerations rather than top end speed. In this article, specifically lateral acceleration was tackled from a physical off-court training with regards to technical training. Tennis players who use the forehand weapon to cover most of the court often run farther for the forehand than backhand, which requires higher acceleration to the forehand. Focus in this article was on physical training with some technical training. Physical training should require elastic unilateral reactive leg strength training and COD movement. Little research exists on unilateral reactive leg strength training which has implications in tennis. A series of tests were recommended but need to be correlated to actual lateral speed and acceleration in future studies.

REFERENCES

Bialik, K. (2014 July 2). Does tennis need a shot clock? Retrieved 7 September 2020 from

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/does-tennis-need-a-shot-clock/

Carboch, J., Placha, K., & Sklenarik, M. (2018). Rally pace and match characteristics of male

and female tennis matches at the Australian Open 2017. Journal of Human Sport and

Exercise, 13(4), 743-751. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2018.134.03

Dintiman, G. (2020). NASE essentials of next-generation sports speed training. Healthy

Learning.

Duthie, G. M., Pyne, D. B., Marsh, D. J., & Hooper, S. L. (2006). Sprint patterns in rugby union

players during competition. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 20(1), 208.

https://doi.org/10.1519/00124278-200602000-00034

Fernandez, J., Mendez-Villanueva, A., & Pluim, B. M. (2006). Intensity of tennis match

play. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(5), 387–391. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.023168

Ferris, D. P., Liang, K., & Farley, C. T. (1999). Runners adjust leg stiffness for their first step on

a new running surface. Journal of Biomechanics, 32(8), 787-794. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00078-0

Ferrauti, A. and Weber, K (2001). Stroke situations in clay court tennis. Unpublished data

Game Inside Group, Tennis Australia (2016 November 24). Djokovic the fastest player in the

world. https://tennismash.com/2016/11/24/gig-djokovic-fastest-tennis-player-world/

Gómez, J. H., Marquina, V., & Gómez, R. W. (2013). On the performance of Usain Bolt in the

100 m sprint. European Journal of Physics, 34(5), 1227. https://doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/34/5/1227

Habibi, A., Shabani, M., Rahimi, E., Fatemi, R., Najafi, A., Analoei, H., & Hosseini, M. (2010).

Relationship between jump test results and acceleration phase of sprint performance in national and regional 100m sprinters. Journal of Human Kinetics, 23(2010), 29-35. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10078-010-0004-7

Hewit, J. K., Cronin, J. B., & Hume, P. A. (2012). Asymmetry in multi-directional jumping

tasks. Physical Therapy in Sport, 13(4), 238-242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2011.12.003

Hoppe, M. W., Baumgart, C., Bornefeld, J., Sperlich, B., Freiwald, J., & Holmberg, H. C.

(2014). Running activity profile of adolescent tennis players during match play. Pediatric Exercise Science, 26(3), 281-290. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2013-0195

Jeffries, I. (2017). Gamespeed: Movement training for superior sports performance. Coaches

Choice.

Kovacs, M. S. (2007). Tennis physiology. Sports Medicine, 37(3), 189-198.

https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200737030-00001

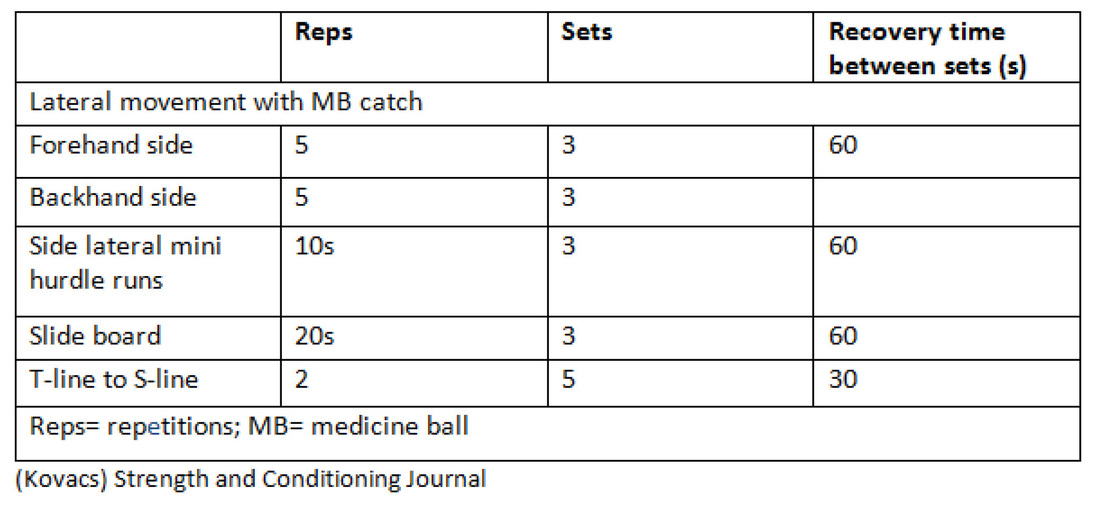

Kovacs, M. S. (2009). Movement for tennis: The importance of lateral training. Strength &

Conditioning Journal, 31(4), 77-85. https://doi.org/10.1519/ssc.0b013e3181afe806

Kovalchik, S. (2017 Jan 26). Rally lengths are down at the Australian Open. Stats on the T.

http://on-the-t.com/2017/01/26/ao2017-rally-lengths/

Lockie, R. G., Schultz, A. B., Callaghan, S. J., Jeffriess, M. D., & Berry, S. P. (2013). Reliability

and validity of a new test of change-of-direction speed for field-based sports: the change-

of-direction and acceleration test (CODAT). Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 12(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7020045

Lockie, R. G., Schultz, A. B., Callaghan, S. J., Jeffriess, M. D., & Luczo, T. M. (2014).

Contribution of leg power to multidirectional speed in field sport athletes. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 22(2), 16-24.

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eamonn_Flanagan/publication/265227430_Researc

hed_Applications_of_Velocity_Based_Strength_Training/links/543690a60cf2dc341db35

e79.pdf#page=17

Mann, J. B., Ivey, P. A., Mayhew, J. L., Schumacher, R. M., & Brechue, W. F. (2016).

Relationship between agility tests and short sprints: Reliability and smallest worthwhile difference in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division-I football players. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(4), 893-900. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000001329

Mann, R.V., & Murphy A. (2018). The mechanics of sprinting and hurdling. R.V. Mann.

Morin, J. B., Samozino, P., Zameziati, K., & Belli, A. (2007). Effects of altered stride frequency

and contact time on leg-spring behavior in human running. Journal of Biomechanics, 40(15), 3341-3348. https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2007.05.001

O’Donoghue, P.G., Liddle, S.D. (1998). A notational analysis of time factors of elite men’s and

ladies’ singles tennis on clay and grass surfaces. Journal of Sports Sciences, 16, 592-3.

Over, S., & O’donoghue, P. (2008). Whats the point: Tennis analysis and why. ITF Coaching

and Sport Science Review, 15(45), 19-21. https://www.itf-academy.com/?view=itfview&academy=103&itemid=1168

Richers, T.A. (1995). Time-motion analysis of the energy systems in elite and competitive

singles tennis. Journal of Human Movement Studies, 28, 73-86.

Sackmann, J. (n.d.). Match charting project: Men’s rally leaders: Last 52. Retrieved 7

September 2020 from http://tennisabstract.com/reports/mcp_leaders_rally_men_last52.html

Sackmann, J. (n.d.). Match charting project: Women’s rally leaders: Last 52. Retrieved 7

September 2020 from http://tennisabstract.com/reports/mcp_leaders_rally_women_last52.html

Sackmann, J. (2016 August 19). Searching for meaning in distance run stats.

http://www.tennisabstract.com/blog/category/distance-run/

Sackman, J. (2020 August 31). What happens to the pace of play without fans, challenges or

towelkids? http://www.tennisabstract.com/blog/category/match-length/

Salonikidis, K., & Zafeiridis, A. (2008). The effects of plyometric, tennis-drills, and combined

training on reaction, lateral and linear speed, power, and strength in novice tennis

players. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(1), 182-191. https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31815f57ad

Si.com Staff (2015 January 25). Daily data viz: Mens court distance covered.

https://www.si.com/tennis/2015/01/25/daily-data-viz-mens-court-distance-covered-australian-open

Young, W. B., James, R., & Montgomery, I. (2002). Is muscle power related to running speed

with changes of direction? Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 42(3), 282-288. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Warren_Young/publication/11281917_Is_Muscle_Power_Related_to_Running_Speed_With_Changes_of_Direction/links/0deec529cfa284fa7d000000.pdf

Weber, K., Pieper, S., & Exler, T. (2007). Characteristics and significance of running speed at

the Australian Open 2006 for training and injury prevention. Journal of Medicine and Science in Tennis, 12(1), 14-17. https://www.tennismedicine.org/page/JMST

Weyand, P., Sternlight, D., Bellizzi, M. and Wright, S. (2000). Faster top running speeds are

achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements. Journal of Applied Physiology, 89, 1991-2000. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1991

RSS Feed

RSS Feed