A few days ago I was walking through our gym and saw three athletes sitting in a circle apparently “stretching.” I took the time to encourage them with their stretching and told them that this should become a habit. Every bit of effort that you put into your training will pay off in the future. Essentially you are training today for tomorrow’s successes.

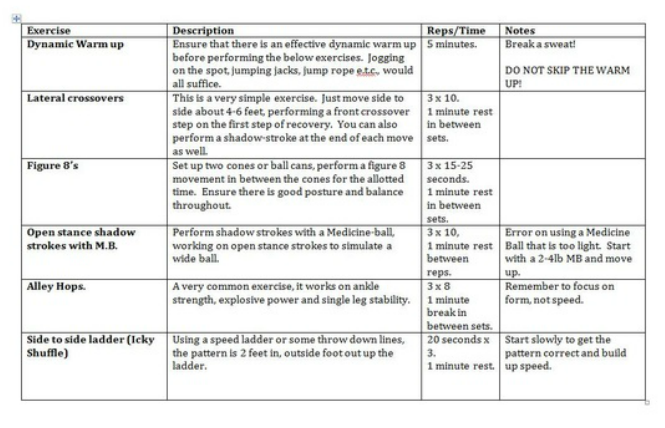

So, where does practice start and end? Many athletes seem to put considerable amount of attention into their training when there is some type of competition, like when playing points or practice matches. But what about the rest of the time, during the more mundane tasks of warming-up or recovery? The old saying is that practice makes perfect. Then it morphed into perfect practice makes perfect. I’m telling you that purposeful practice will lead to success on the court. This must transcend not only during times where the athlete wants to be present, but also during any activity that is adding in the advancement of their career. Without the attention and intention of the athlete, they will not progress as much as perhaps they could.

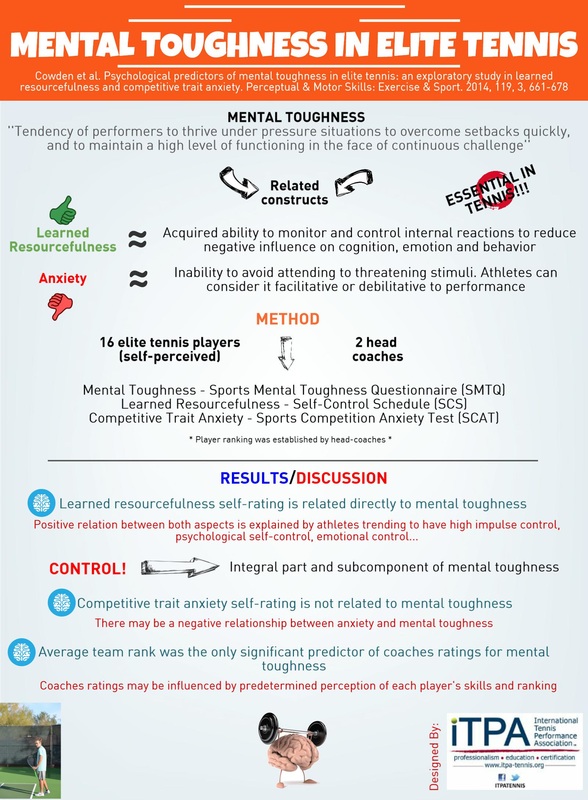

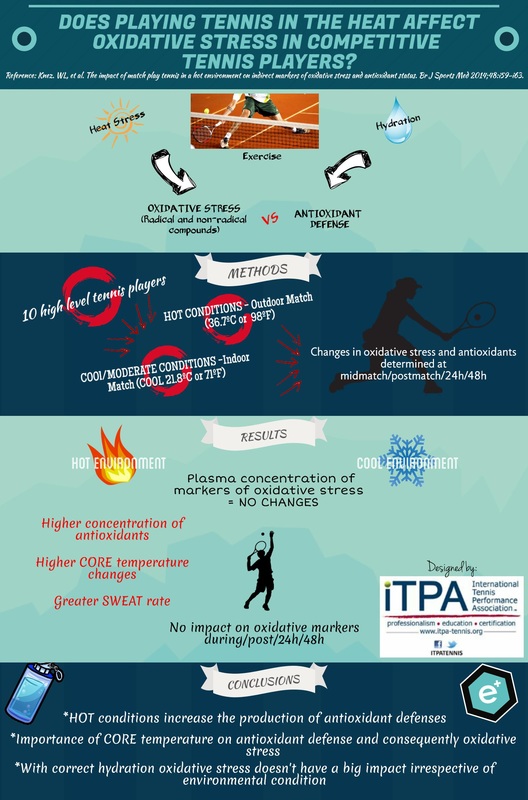

So again, when does it start and end? I believe that for any athlete that has expressed a desire to have a career in sports, practice doesn’t start or end, it’s always there. Every facet of an athlete’s life aids in their development as a complete person and player. The athlete must have ownership of their path. Every little thing counts, whether it’s hydrating properly prior to training, getting enough sleep or working on the mental aspect of their game. It’s like a recipe, if any portion of it is left out, you cannot predict the outcome. If you’re trying to bake a chocolate cake and you leave the chocolate out, I assure you that it will not be what you expected. In life however, there are no guaranties, even if all aspects of training are perfected. But it is good to stack the odds in your favor.

Dean Hollingworth, MTPS, CSCS

[email protected]

Twitter: @deaner99

RSS Feed

RSS Feed